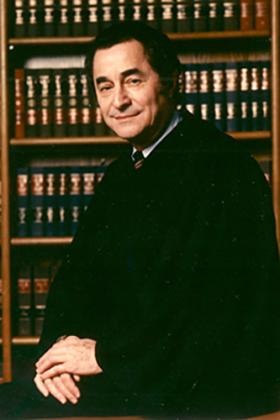

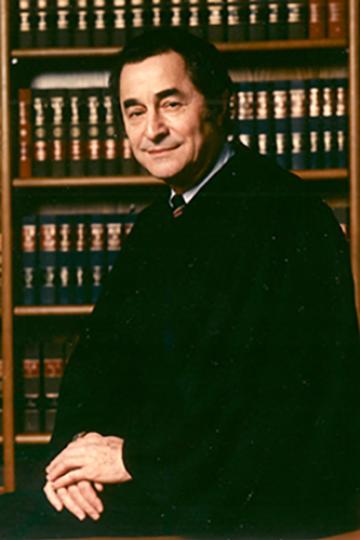

- Term: Aug. 10, 1979 - June 30, 1996

- Status: Deceased - July 23, 1996

Introduction

It’s hard to imagine anyone referring to Robert Wilentz as "Bobby," sort of like calling Arthur T. Vanderbilt "Artie." It just doesn’t fit. Like Vanderbilt, Wilentz was a judicial leader whose accomplishments have been recognized by lawyers, scholars and judges across the nation.

A World War II veteran who received his undergraduate degree from Harvard, and his law degree from Columbia University, Wilentz was driven - determined to excel at all he did. The son of David Wilentz, the prosecuting attorney in the famous "Lindberg Baby Trial" of 1935, and one of the more feared Democratic power brokers of Twentieth Century New Jersey, there was little question that Robert would pursue a legal career. "Pursue" is an understatement. Much like Chief Justice Vanderbilt, mere mortals will never understand how he found the time to do all that he did throughout his life. During his 27-year legal career, Wilentz was: a highly-respected attorney; involved in many significant Bar Association matters; a member of influential committees appointed by the Supreme Court; and active in county and state politics, serving two terms in the State Legislature.

Upon his appointment as Chief Justice, his pace almost seemed to quicken. Robert Wilentz was someone who understood power and how to wield it, yet never lost his reverence for the majesty of the law and its critical role in our society. From his perch of Chief Justice, which the 1947 Constitution made one of the most powerful state judges in the nation, Wilentz saw gaps in New Jersey’s court system that needed filling, and the problems of ordinary people which only the law could address. He raced to make things right. He was a lawyer’s lawyer, and a judge’s judge. Robert Wilentz’s accomplishments as Chief Justice are breath-taking. He is a role model for judges everywhere.

Overview of Years as Chief Justice

Robert Nathan Wilentz served as Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court from August 10, 1979 to July 1, 1996. He replaced former Chief Justice Richard J. Hughes, who had reached the mandatory retirement age of 70.

When Mr. Wilentz became Chief Justice, the New Jersey Supreme Court enjoyed the reputation of being one of the finest in the country and he strove successfully to maintain and strengthen that reputation throughout his tenure. He achieved this through insisting on "the highest standards" for lawyers, judges, and himself, as he oversaw the complete reorganization of New Jersey’s court system to modernize and to improve its efficiency and effectiveness.

Upon taking office, Chief Justice Wilentz found that caseloads in the lower courts had become massive and complex, overwhelming the existing calendar management systems to the point where they no longer worked efficiently.

Areas he sought to strengthen were: case processing systems; antiquated technology; weak vicinage management; and a court culture unresponsive to the current needs. Fortunately, the New Jersey Constitution of 1947 provided the authority and the tools with which to address these issues, namely rule-making authority and providing centralized powers in the Supreme Court and the Chief Justice as administrative head of the courts.

Recognized nationally as both an innovative and pragmatic jurist, Wilentz directed the Court through a period of extraordinary change. Throughout his tenure, Wilentz worked to streamline policies and practices of the State courts to guarantee access to all and instill public trust and confidence. These changes were instrumental in promoting Wilentz’s vision of social progress and equality.

- Leading the "Wilentz Court" in the issuance of pivotal rulings respecting a citizen’s rights to just treatment under the law on everything from racial and sexual discrimination; conduct of judges and lawyers; and affordable housing; to "thorough and efficient" public education; social host liquor liability; and the death penalty;

- Establishing four manageable court divisions: Civil, Criminal, Family, and General Equity, and working with the Legislature to establish a separate Tax Court;

- Reorganizing the Appellate Division and realignment of the trial courts into fifteen vicinages with new boundaries, and initiating improvement and modernization of the municipal court system;

- Enlarging Assignment Judges’ responsibilities and upgrading Trial Court Administrators’ roles, and introducing new management systems, all to improve service;

- Establishing a Speedy Trial Program, a comprehensive complementary dispute resolution system, and achieving unification and State funding of the New Jersey court system; and

Many of the details of how Chief Justice Wilentz reshaped New Jersey’s courts are set forth in: Ronald J. Fleury, Pamela Brownstin & Jeffrey Kanige, How Wilentz Changed the Courts, 7 Seton Hall Const. L.J. 2, 411-432 (Winter 1997).

Personal History

Robert Wilentz was born in Perth Amboy, New Jersey on February 17, 1927, to David T. and Lena Wilentz. He graduated from Perth Amboy High School and attended Princeton University before serving in the United States Navy as Seaman First Class from 1945 to 1946. After military service, he graduated from Harvard in 1949 and received his law degree from Columbia University in 1952. Mr. Wilentz married Jacqueline Malino in 1949. They had three children: James Robert born in1951, Amy born in 1954, and Thomas Malino Wilentz born in 1959.

Chief Justice Wilentz’s father, David T. Wilentz, was the New Jersey Attorney General who prosecuted Bruno Richard Hauptmann for the Lindbergh kidnapping which occurred in 1932. This prosecution which was the first criminal case tried by David Wilentz, took place in 1935, the year following his appointment

As the six-week trial in Flemington, New Jersey continued, the Attorney General garnered international attention. Newspapers and radio stations worldwide reported the proceedings daily. The fame resulting from the trial helped expand his influence within the New Jersey Democratic Party, and he became one of the state’s most powerful politicians.

Robert Wilentz was admitted to the Bar and began practicing law in 1952. For many years he was the managing partner of Wilentz, Goldman & Spitzer in Perth Amboy. The firm’s principal officers included his father and his brother, Warren W. Wilentz. During his career, he was a member of the Middlesex County, New Jersey, and American Bar Associations; the Federal Bar Council; and the World Peace Through Law Center. He was a Fellow of the American Bar Foundation and the American College of Trial Lawyers, and served as Associate Editor, New Jersey Law Journal, and a Member of the Board on Trial Attorney Certification (appointed by the Supreme Court. In addition to two terms as Democratic Assemblyman in the New Jersey State Legislature, representing Middlesex County from 1965 through 1969; serving on the Appropriations Committee, the Education Committee and the Public Employees’ Grievance Procedure Commission; he served on numerous county, state and Federal Bar Committees.

Appointment as Chief Justice

On April 5, 1979, Governor Brendan T. Byrne nominated Mr. Wilentz to the position of Chief Justice. In announcing the nomination, Governor Byrne said he "was looking for someone with the depth of a Weintraub, the authority of a Vanderbilt, and the compassion of a Hughes." Brian O’Reilly, The Next Chief Justice, New Jersey Magazine, April 1979, p.19.

At his swearing in ceremony, Wilentz expressed his basic approach to his new role. He spoke "not just for myself, but for the court which I have been asked to lead. Together we will try our best to preserve the traditional quality of New Jersey’s judicial system. We will also try to improve it, of course, but if we succeed in preserving that tradition and that quality, we will be satisfied — and so will those who understand how great that tradition is, and how superior that quality."

Chief Justice Wilentz went on to explain his view of the responsibilities of New Jersey’s Supreme Court:

The powers of the Court go far beyond deciding what the law of New Jersey is. The Supreme Court commands the entire resources of the judicial system, from business machines to courthouses, from study committees to judicial conferences; it has command over the practice of law, over lawyers, over the delivery of legal services; it has command and complete control over the practice and procedure in every court in this State; it commands a very substantial administrative organization; and finally, it commands, to an extent greater than any other state, all judicial personnel, from every clerk to every judge, at the trial level, at the appellate level, in the towns, cities, counties, throughout the State. [Hon. Robert N. Wilentz, C.J., Swearing In Ceremony, April 2, 1979, Remarks by Chief Justice Wilentz, 49 Rutgers L. Rev. 637 (Spring 1997).]

Associate Justice Daniel O’Hearn has described Chief Justice Wilentz’s:

. . . clear vision of the role of the judiciary in our society. He did not regard courts as spectators of public events, detached from the constitutional guarantees that they must enforce. He would not allow the courts to become a tool to suppress society’s less privileged. The Chief had the resolve to enforce the constitution when its guarantees were ignored. Hon. Daniel J. O’Hern, Tribute: The Honorable Robert N. Wilentz, 7 Seton Hall Const. L.J. 2, p. 333 (Winter 1997).

Associate Justice Gary S. Stein characterized Wilentz’s determination to preserve an independent judiciary:

At the root of his conviction was the recognition that the judiciary is often called on to render decisions that will be unpopular or misunderstood by the general public, and that public displeasure about specific decisions inevitably exerts either express or subtle pressures on judges to bend to the public’s will. He was determined to provide our state’s judges with every possible indicium of autonomy and independence, the better to enable the judiciary to resist those pressures. To that end, he insisted on the strictest separation of the judiciary from any vestige of politics, and fought tenaciously to assure the reappointment with tenure of qualified judges. [Id. at 341.]

Commitment to Judicial Independence

Wilentz recognized that exercising their responsibility to adjudicate the most contentious legal issues, made judges lightning rods for intense criticism. He valued the competence and independence of the judiciary to perform in the public interest.

His brother, Warren, often spoke of the Chief’s commitment to never permitting anyone from the outside to influence his opinion: "No public opinion could force him to do something he didn’t think was right. Nobody in the executive department could make him do something that he didn’t think was right and was good." This philosophy was reflected in his leadership in initiating professional conduct reforms during his tenure. Some of these are examined in Michael P. Ambrosio & Denis F. McLaughlin, The Redefining of Professional Ethics in New Jersey Under Chief Justice Robert Wilentz: A Legacy of Reform, 7 Seton Hall Const. L.J. 2, p. 351-410 (Winter 1997).

The extent and impact of the Chief’s principles were underscored by the controversy surrounding his tenure reappointment in 1986. Democratic Governor Byrne had initially appointed Mr. Wilentz. Republican Governor Thomas H. Kean reappointed him. Opposition to the Wilentz reappointment came from seven Republican State Senators who urged Kean to appoint a Republican. In addition, they disagreed with some of the Wilentz Court’s decisions. In renominating Wilentz, the Governor concurred with the Chief Justice’s principles when he stated:

My feeling is that he has served honorably, and on every ground that I have a responsibility to consider, he should be worthy to continue as chief justice. I do differ strongly with anybody who would imply that politics has ever entered into the court of this chief justice or this court, either now or in the past. If any judge in the state is worried about how he should make a decision that would affect his or her renomination, then the quality of justice is not going to be what you and I would want it to be in the State of New Jersey.

By their statements and by their actions, Chief Justice Wilentz and Governor Kean showed they valued preservation of the integrity and honesty of an independent judiciary.

During the hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, opponents switched their opposition to Wilentz’s residence. He rented an apartment in New York City, and another in Perth Amboy, NJ and had a home in Deal, NJ. Wilentz had spent many nights in New York since 1980 to be with his wife, a cancer patient receiving extensive treatment. Wilentz said he was a New Jersey resident, voted in New Jersey, and paid New Jersey income taxes. He also stated his belief that the Chief Justice should be a New Jersey resident. The Committee cleared the nomination by a 9-2 vote. The final reappointment vote in the Senate was 21-19 in favor of reappointment.

Former Governor and Chief Justice Richard J. Hughes called Chief Justice Wilentz "a restless seeker for justice." Wilentz emphasized the importance of judicial independence. Speaking before Legal Services of New Jersey on June 22, 1995:

We do not want the public to wonder or worry if the judge or the Judiciary favors some special interest or some controversial issue associated with that interest. The Judiciary should conduct itself in a way that reinforces the public’s confidence in our impartiality. Legal Services of New Jersey Eleventh Annual Justice Awards Reception, Speeches by Chief Justice Wilentz, 49 Rutgers Law Review 1186 (Spring 1997).]

In the First Annual Chief Justice Joseph Weintraub Lecture at Rutgers Law School on April 13, 1981, Wilentz addressed the role of standards of judicial conduct beginning with a prohibition found in the New Jersey Constitution:

It prohibits judges, while in office, from engaging in the practice of law or other gainful pursuit. . . . [I]t is clear that the judges in this state are to have but one master, one employer, and only one to serve. It is the public to whom the judge owes his complete loyalty and the prohibition assures that there will be neither a conflicting financial interest nor even a conflicting claim on the judge’s time. Besides its practical impact of requiring the judge to devote all of his energies to the judiciary and of minimizing financial conflicts, the prohibition does something just as important: it calls for exclusive attention to the bench; the consequence is devotion, devotion not only of time, but of spirit. It is this devotion that I believe is the foundation on which our tradition of judicial integrity has been built. 49 Rutgers L. Rev. 800 (Spring 1997).]

Wilentz also described the enforcement of the Code of Conduct through the Supreme Court’s Advisory Committee on Judicial Conduct. He noted the important words of Chief Justice Hughes on the creation of the Advisory Committee in 1974, "In a free society, the court’s influence, acceptance and power alike rest, not only on the Constitution and statutory law, but upon public confidence in its probity, objectivity and freedom from outside pressure of whatever kind. This applies to all courts, including the hundreds of municipal judges." [Id. at 807.]

In concluding the Weintraub Lecture, Wilentz emphasized the important intertwining of judicial independence and judicial conduct in delivery of justice to the citizens of New Jersey, "Judicial conduct has a meaning beyond the good conduct of judges. For citizens, rightly or wrongly doubtful of the integrity of government to the point of cynicism, the Judiciary still remains their hope, that one place in government which they still seem to trust, or at least I hope they do. We must, as never before, justify this faith." [Id. at 811.]

The "Wilentz Court" and Social Justice

In a series of decisions issued over the years by the Wilentz Court, the Chief Justice worked tirelessly to justify the public’s confidence. Regarded by some as one of the most highly recognized courts in the nation, the Wilentz Court established precedents that are still recognized today.

Under Wilentz, the New Jersey Supreme Court became the first State court to issue a mandate on notification laws, which was subsequently enacted by the federal government and other states. Many states followed the blueprint that the New Jersey Supreme Court established under the direction of Wilentz, thus, creating an indelible legacy.

Wilentz was in the forefront in confronting legal issues, and he influenced the New Jersey practice of law through decisions that promoted his vision of social change and equality. As a jurist Wilentz was an intense advocate of preserving the independence and impartiality of the judiciary, recognizing that the role of the court is to adjudicate matters absent personal bias or external influence. As a progressive visionary who sought to eliminate inequality, Wilentz crafted decisions that expanded existing doctrine and promoted equality and fairness. He employed a scholarly approach, second to none and recognized the need to render socially unpopular decisions when doing so would bring society to a more equitable place. This often resulted in the expansion of constitutional protections enumerated in the State Constitution and the United States Constitution.

No greater examples can be found than in Wilentz’s groundbreaking, although at times socially unpopular, decisions on judicial and social conduct, professional conduct of attorneys, and local governance.

Wilentz guided his fellow jurists, attorneys, and the public through decisions that shaped not only the conduct of the judiciary, but of society as a whole. This is best exemplified in the legacy of Doe v. Poritz, 142 N.J. 1 (1995). At that time, there was a public outcry after the murder of Megan Kanka, and the New Jersey legislature brought forth the first statute to mandate public notification of convicted sex offenders. The legislation faced constitutional challenges specifically related to the two bills associated with the law: (1) the Registration Law and (2) the Community Notification Law.

Wilentz, tasked with writing the opinion, recognized both sides of the controversial law, but concluded that the law was constitutional. The Court held that so long as the means of protection employed by a society are reasonably designed to protect citizens, those means are not unconstitutional

The Court found that the legislation’s intent was not to punish and its sole purpose is regulatory. The Court further held that the State’s practice of notification was subject to judicial review where an offender timely challenges that notification process. In the absence of a challenge, the Court held that the notification guidelines set forth by the Attorney General and the tiered notification system for offenders, would apply.

Wilentz saw the intent behind the law as remedial, not punitive, while recognizing that it could have unintended consequences for the registered individual. Thus, Wilentz sought to give those individuals some protection, thereby requiring judicial review where applicable. Since Doe v. Poritz, many other jurisdictions, including the federal government, have passed their own version of Megan’s Law, solidifying Wilentz as a pioneer in balancing public interest against private rights.

With the decision in State v. Kelly, 97 N.J. 178 (1984), Wilentz further advanced society’s changing composition by giving recognition to the then-novel psychological theory of "battered spouse syndrome." In Kelly, the Wilentz Court reviewed the exclusion of expert testimony on the theory of battered spouse syndrome by the trial court. Wilentz held that battered spouse syndrome is an appropriate subject for expert testimony and that, despite the newness of the theory, expert testimony provided in the case met the requirements for admittance.

With this holding, Wilentz not only legitimized battered-spouse syndrome as a defense in criminal cases, but recognized that some issues that may appear simple on the surface are more complex when examined in depth. As he noted in his opinion, myths regarding battered-women can be easily reinforced when brought forth by laymen, including prosecutors. Allowing expert testimony can quell these myths and give the jury a more nuanced and credible view of how battered-woman syndrome works.

In State v. Powell, 84 N.J. 305 (1980), the Wilentz Court examined the second-degree murder conviction of a police officer. The officer argued that the lower court erred by failing to instruct the jury on an alternate charge of manslaughter. The defense argued that sufficient evidence existed at trial to support the conclusion that the "killing was done in the heat of passion resulting from reasonable provocation." Ibid. Wilentz’s decision in Powell was two-fold. It formally recognized that the passion/provocation defense associated with voluntary manslaughter includes "imperfect self-defense," which is the exercise of "self-defense that is provoked by an act that clouded the defendant's perceptions as to the imminence of danger. Id. at 312.

Additionally, the Powell decision expands upon judicial duties. Wilentz held that evidence of passion/provocation and imperfect self-defense should not only be used to support a manslaughter charge, but also to rebut malice required for a second-degree murder charge. Id. at 314. As the Powell decision instructs, the role of the judge is not to simply to referee a case but to be an active representative of the law.

With this decision, Wilentz established the precedent that a judge is dutifully obligated to give criminal jury instructions on all possible outcomes, thereby giving the jury the opportunity to reach the correct outcome, not the one that is favorable to the adversarial system. In doing so, justice and societal interests as a whole are furthered. Id. at 19.

Death Penalty

In State v. Ramseur, 106 N.J. 123 (1987), the defendant challenged the constitutionality of New Jersey’s capital punishment law under the Federal and State Constitutions. In a lengthy opinion, while holding capital punishment constitutional, the Court held that critical portions of the trial court’s instructions in the sentencing proceeding were erroneous. The Court reversed the death sentence and remanded the matter to the trial court for a specific term of years with no parole eligibility for thirty years.

Wilentz’s sixty-eight page opinion includes a Table of Contents that includes the Facts, the Constitutionality of the Death Penalty Statute, Pre-Trial, Trial and Sentencing issues, Prosecutorial Conduct, Proportionality Review and the Conclusion. Under each subject, subcategories are listed. The conclusion, in addition to ruling on the constitutionality of the statute, importantly, recognized the separation of power between the three branches of government:

It is not for this Court to pass on the wisdom or the ultimate morality of the death penalty. That issue is for the Legislature and the Governor, and for them alone. Our function is to determine whether their decision and the law implementing it are constitutional, and thereafter to review cases in which the death penalty is applied. We find the Act constitutional in all respects but reverse the imposition of the death penalty in this case for the reasons set forth above, and remand the matter for resentencing by the trial court in accordance with this opinion. We affirm the murder conviction. [Id. at 331.]

Justice Handler wrote a lengthy dissenting opinion. While he addressed a number of issues, he noted, "the most significant area of disagreement relates to the constitutionality of the capital murder-death penalty statute. Id. at 345.

The Legislature’s Death Penalty Commission, in its final report acknowledged that "Abolition of the death penalty will eliminate the risk of disproportionality in capital sentencing." N.J. Death Penalty Commission, New Jersey Death Penalty Study Commission Report 7 (2007), p. 46.

On December 17, 2007, New Jersey was the first state to legislatively repeal the death penalty. Instead, "execution was replaced by life imprisonment without parole." George W. Conk, Herald of Change? New Jersey’s Repeal of the Death Penalty, 33 Seton Hall Legis. J. 21 (2008), p. 22. The vote by the Senate to repeal the statute was by only one vote. "The following day, the United Nations General Assembly voted to place a moratorium on executions." Id. at 23.

Social Host Liquor Liability

In Kelly v. Gwinnell, 96 N.J. 538 (1994), Wilentz advanced public policy by imposing liability on a social host who serves liquor to a knowingly intoxicated person who then operates a motor vehicle. The Gwinnell decision effectively makes the social host jointly liable to an injured third party permitting a claim for compensation when injuries result from intoxication.

With this decision, Wilentz placed the public policy of protecting third parties against drunk-drivers over social engagement by ascribing a duty of care on social hosts to ensure that guests who become intoxicated do not drive drunk. This decision seeks to afford fair compensation to victims of drunk driving, and although Wilentz recognized that there existed no assurances of a significant effect as a result of this decision, it demonstrates his recognition that the Court should act, whenever permissible, to protect innocent persons from harm.

The decision in Kelly prompted the Legislature to create a commission to study the question of host liability, known as the Commission on Alcoholic Beverage Liability. On September 18, 1985, the Commission issued its Final Report and recommended legislation to clearly establish the circumstances under which a social host has provided alcoholic beverages. Componile v. Maybee 273 N.J.Super. 402 (Law Div.) 1994.

The statute ultimately adopted by the Legislature (see N.J.S.A. 2A:15.5.6), established standards for determining liability on the social host. In summary, the Legislation defined who is a "social host" and outlined the responsibilities the host of a party has when they observe a guest to whom they have served alcoholic beverages and has become "visibly intoxicated." As noted by both the Wilentz Court and the Legislature, it is reckless for a host to continue serving alcoholic beverages to someone whose sobriety is questionable. To continue serving alcoholic beverages to such a person poses risk of injury to the life and property of others.

The culmination of the Kelly decision in remedial legislation illustrates the three branches of government working together to ensure enlightened standards of societal conduct.

Professional Responsibilities of Lawyers

In addition to his dedication to the administration of justice to benefit all citizens of our State, Wilentz was committed to strengthening public trust and confidence in the work of the courts. This commitment was present in his pivotal decisions regarding the professional responsibilities of attorneys.

In Madden v. Delran, 126 N.J. 591 (1992), the plaintiff, a partner in a New Jersey law firm, was assigned by the Municipal Court of Delran Township to represent an indigent defendant. After the subsequent trial, the plaintiff submitted a bill for his services to the Township of Delran, which the Township refused to pay. The plaintiff and his partners in the firm brought an action against Delran Township alleging the assignment without compensation for services 1) constitutes a taking of private property without just compensation; 2) is unduly burdensome; 3) violates the firm’s equal protection rights; 4) constitutes involuntary servitude; and 5) fails to ensure indigent defendants effective assistance of competent counsel.

In declining to require the municipalities to pay attorneys assigned to represent indigent defendants, the Court held that going forward, counsel shall be assigned to each vicinage strictly in accordance with the mandate of Rule 3:27-2. Assignment by any Municipal Court for pro bono representation of indigent defendants constitutionally entitled to such representation was to be made strictly in accordance with the list required by the court rule.

Madden serves as the cornerstone of pro bono representation for indigent parties by licensed attorneys in New Jersey. The Court’s decision in Madden established the requirement that New Jersey attorneys, with very few exceptions, must be available for pro bono assignments to represent indigent parties. In doing so, the Court established the first pro bono service requirement for attorneys in the United States.

In re Wilson, 81 N.J. 451 (1979), a matter regarding attorney discipline, departed from previous precedent regarding attorney disbarment in matters where an attorney knowingly misappropriates client funds held in trust, reasoning that "the public confidence was so important that mitigating factors will rarely override the requirement of disbarment and that if public confidence was destroyed, the bench and the bar will be crippled institutions."

This was a marked departure from the previous Court that permitted leniency in disciplinary matters where certain mitigating factors existed. In his opinion, Wilentz held that the maintenance of public trust and confidence in the "Court and in the bar as a whole requires the strictest discipline in misappropriation cases" thus, generally all cases of misappropriation "shall result in disbarment." Id. at 61.

In In re Petition of Felmeister & Isaacs, 104 N.J. 515 (1986), a law firm sought review of the Rules of Professional Conduct governing attorney advertising, seeking to invalidate Rule 7.2(a) on the basis that it violated the First Amendment Right to Freedom of Speech. The firm alleged that the broad application of Rule 7.2(a), which prohibits the use of drawings, animations, dramatizations, music, or lyrics and required all advertisements to be presented in a dignified manner, was contrary to the rights afforded under the United States Constitution. Id. at 516.

The Court amended the provisions of the Rule by limiting the restrictions to television advertisements and by eliminating the dignified manner requirement. Wilentz, on behalf of the Court, held that the new requirement that an advertisement be predominately informational served the substantial state interest of assuring that consumer decisions in selecting counsel were reasonable."

At the time of this decision, the rules on attorney advertising were in their infancy. The Court openly acknowledged that its effort to find the "proper balance was "undertaken with an open mind and a willingness to change as we learn more, perhaps, of a better balance." Id. at 518.

The Wilentz Court played an integral role in defining the standards of the practice and professionalism required by attorneys admitted to practice law in the State of New Jersey. The legal principles created by Madden, In re Wilson, and In re Petition of Felmeister & Isaacs continue to serve as a framework for attorney ethics and professionalism more than two decades later.

Affordable Housing

In Southern Burlington County N.A.A.C.P. v. Mount Laurel Tp., 67 N.J. 151, 187 (1975) (hereinafter Mount Laurel I), an action was brought against the township of Mount Laurel on the ground that the land use regulations of the township unlawfully excluded low and moderate-income families.

Justice Hall, writing for the majority, held "as a developing municipality, Mount Laurel must, by its land use regulations, make realistically possible, the opportunity for an appropriate variety and choice of housing for all categories of people who desire to live there, of course including those of low and moderate income."

Unfortunately, despite the decision in Mount Laurel I, "eight years later the town of Mount Laurel remained afflicted with blatantly exclusionary zoning ordinances, forcing the New Jersey Supreme Court to revisit the issues in Mount Laurel II, 92 N.J. 158 (1983). Kirk Addes, The Fate of Affordable Housing Legislation In New Jersey Christie’s Proposed S-1 Legislation Threatens To Undo the New Jersey Supreme Court Decisions in Mount Laurel I and Mount Laurel II, 36 Seton Hall Legis. J. 82 (2011).

In Mount Laurel II, Wilentz expanded upon the original Mount Laurel decision, which outlined a doctrine requiring that municipalities’ land use regulations provide for low and moderate-income housing. While the Mount Laurel I decision prohibited economic discrimination against the poor by the state and municipalities in the exercise of their land use powers, the decision in Mount Laurel II, set forth specific requirements that every town in New Jersey must provide its "fair share" of the regional need for low and moderate income housing. Ibid.

The decision in Mount Laurel II set forth the principle, that municipalities cannot manipulate zoning regulations to preclude people from residing in an area solely because of economic status. Importantly, Wilentz recognized that society was strengthened when persons from all socio-economic background could reside together. Ibid

Public Education

In Abbott v. Burke, 119 N.J. 287 (1990), the Wilentz Court heard a constitutional challenge to the Public School Education Act of 1975 (the "Act") and held the Act unconstitutional as applied to poorer urban school districts. The Court reasoned that the constitutional mandate, dating back to 1875, to provide a "thorough and efficient" education in poorer districts had not been fulfilled. Id. at 384.

The Wilentz Court ruled that the Act had to be amended, or new legislation passed, to assure that poorer urban districts' educational funding was substantially equal to that of richer districts. The Court determined that poorer urban districts were required to have a budget per pupil sufficient to address their special needs. Id. at 385. With this decision, Wilentz reinforced the basic rights that every New Jersey child is entitled to an education that prepares them for society. The Abbott decision led New Jersey to enact universal preschool in the state’s poorest districts, spurred construction of new schools throughout New Jersey, and provided increased programs for the disadvantaged throughout the state. The Abbott decision remains a cornerstone in how New Jersey establishes funding in urban and suburban schools.

"Baby M"

In re Baby M, 109 N.J. 396 (1988), addressed profound social issues concerning the contract of a surrogate mother to deliver custody of the child that she had borne to the biological father. The decision set forth the controlling principles of law balancing the interests of mother, child, and father.

On March 27, 1986, Mary Beth Whitehead gave birth to a daughter, whom she named Sara Elizabeth Whitehead. However, within 24 hours of transferring physical custody, Ms. Whitehead went to the Stern Family and demanded that the baby be returned to her, allegedly threatening suicide. Ms. Whitehead subsequently refused to return the baby to the Sterns and left New Jersey, taking the infant with her.

On March 31, 1987, a Superior Court Judge formally validated the surrogacy contract and awarded custody of Baby M to the Sterns under a "best interest of the child analysis". On February 3, 1988, however, the Court, led by Wilentz, invalidated surrogacy contracts as against public policy, but in dicta affirmed the trial court’s use of a "best interest of the child" analysis and remanded the case to the Family court. On remand, the lower court awarded the Sterns custody and Ms. Whitehead was granted visitation rights.

IOLTA

Being aware that achieving equal access to our courts also required significant funding, Wilentz convinced the Supreme Court to adopt Interest on Lawyers Trust Accounts ("IOLTA") to help fund Legal Services. This was a major step forward in improving equal access to justice for the poor in New Jersey. A second major step was the effort by the Chief Justice to foster more judicial diversity and further help close the justice gap between the poor or otherwise disadvantaged and the privileged.

As observed by former Associate Supreme Court Justice James H. Coleman, Jr. in the Seventh Wilentz Lecture to Legal Services of New Jersey (March 28, 2011), when Robert Wilentz became Chief Justice in 1979, all of the Associate Justices of the New Jersey Supreme Court were white males. When Mr. Wilentz passed away, shortly after his retirement in 1996, the Supreme Court included a female Chief Justice, a female Associate Justice, and an African-American Associate Justice. In addition, the Appellate Division then included two African American, one Latino, and seven female judges. There also was one African-American Assignment Judge.

Judicial Diversity

At the swearing-in ceremony for Justice Coleman on December 16, 1994, Wilentz expressed the importance of judicial diversity in enhancing both the appearance and the actuality of equal justice and equal access:

This is a momentous day in the history of our Judiciary. For the first time ever, we will have an African American on our highest court. Young children on our playgrounds, little kids starting school, adolescents just growing up, will see a bright ray of hope that they didn’t see before. And so will their older brothers and sisters. And grown-ups, Black, Hispanic, Asian American, and others, all of them. . . . will feel better about our justice system, and will have some more confidence in it. Everyone should celebrate this day, for it is a good day for all of us, a good day for society. [42 Rutgers Law Review 1173 (Spring 1997).]

Wilentz's deep commitment to equal justice and equal access is revealed by his actions when, in 1982, Superior Court Judge Marilyn Loftus raised the issue of gender bias in the Courts with both Wilentz and the Administrative Director of the Courts, Robert D. Lipscher.

In response to Judge Loftus, Wilentz appointed the Supreme Court Task Force on Women in the Courts, in June of 1982, with a one-year assignment to report findings at the next Judicial College. Wilentz charged the Task Force with investigating: …" the extent to which gender bias exists in the New Jersey judicial branch . . . . We want to make sure, in both substance and procedure, that there is no discrimination whatsoever against women - whether they are jurors, witnesses, judges, lawyers, law clerks or litigants." Learning from the New Jersey Supreme Court Task Force on Women in the Courts: Evaluation, Recommendations and Implications for Other States, 12 Women’s Rts. L. Rep. 313-85 (Fall 1991).

The Task Force presented its report and recommendations, at the 1983 Judicial College, in which they identified problems in the following selected areas for which they had collected data: damages, domestic violence, juvenile justice, matrimonial law, sentencing, interactions in the court and professional environments, and court administration.

The Task Force focused its investigation on three specific issues:

(1) Do gender-based myths, biases, and stereotypes affect the substantive law and/or impact upon judicial decision-making?

(2) Does gender affect the treatment of women and men in the legal and judicial environment (courtroom, chambers, professional gatherings)?

(3) If so, how can judges affirmatively ensure equal treatment for women and men in the courts? Id. at 316.

At the conclusion of the Task Force presentation, Wilentz stated:

There is no room for gender bias in our system. There’s no room for the funny joke and the not-so-funny joke, there’s no room for conscious, inadvertent, sophisticated, clumsy, or any other kind of gender bias, and certainly no room for gender bias that affects substantive rights. There’s no room because it hurts and it insults. It hurts female lawyers psychologically and economically, litigants psychologically and economically, and witnesses, jurors, law clerks and judges who are women. It will not be tolerated in any form whatsoever.

Wilentz considered the findings of the Task Force to be so significant that he extended the Task Force for an indefinite time to further investigate gender bias in the court system and make additional recommendations. The Task Force published its full First Year report in 1984 and its Second Report in 1986.

Wilentz’s continual, vigorous, highly visible personal support of the Task Force and its recommendations was critical to its accomplishments. The article cited above (Learning from the New Jersey Supreme Court Task Force on Women …) reviewed the accomplishments and impact of the Task Force during its first six years and provided recommendations for future efforts.

This evaluation study found that over the first six years of its existence the Task Force: …" efforts have brought about important changes in the New Jersey Courts and inspired a nationwide gender bias task force movement . . . . The New Jersey Supreme Court Task Force on Women in the Courts can rightly claim to have played a pivotal role in American judicial reform.". The evaluation study concluded that the greatest impact of the task force was in reducing gender bias both in the courtroom and in professional environments. More specifically, within New Jersey the Task Force created "a climate within the court system in which the nature and consequences of judicial gender bias are both acknowledged to exist and understood to be unacceptable in the New Jersey courts."

In response to one of the recommendations of the evaluation study, the Chief Justice and the Supreme Court magnified their national leadership in addressing gender bias issues in the court system by replacing the Task Force on Women in the Courts with a permanent Supreme Court Committee on Women in the Courts. This Committee has a permanent staff and is charged with implementing recommendations to eliminate gender bias as well as being responsible for the entire range of gender bias problems. In speaking at the occasion recognizing "The Tenth Anniversary of the Task Force on Women in the Courts" on December 9, 1992, Wilentz made the following remarks:

I want to congratulate you on your tenth anniversary for your great work. You have started to bring equality to women in the courts of New Jersey, and that means fair treatment, equal treatment, respect, and dignity. And you have brought the same thing to women in practically every court in the nation. You have been enormously effective...

Freedom from mistreatment is an absolute minimum condition, but we aim much higher. We aim for real equality, equal opportunity, equal treatment, respect — not only no discrimination, but no differentiation. We’re the same — we’re not just entitled to be treated like we’re equal — we are equal. … There is a lot to do, and it’s going to get done, and that’s why the Court appointed a permanent standing committee on women in the courts. … On behalf of the Supreme Court of New Jersey, I thank you for everything you have done, not just for women but for the judiciary. You’ve made us a better institution. Make sure we stay that way. [42 Rutgers L. Rev. 3, 1133-34 (Spring 1997).]

Complementary Dispute Resolution

Another important goal of Wilentz, related to equal justice and equal access, was to make affordable, efficient and expeditious legal services available to all citizens. He exerted efforts for more than a decade to establish a program of complementary dispute resolution ("CDR") for the state’s courts. His appointment of the Supreme Court Committee on Dispute Resolution Programs in May of 1983 began those efforts. The function of that Committee was to review needs and alternative existing dispute resolution approaches and to plan for a complementary process to operate within the court system in conjunction with the traditional adjudication process. Hon. Marie L. Garibaldi, J., Chief Justice Robert Wilentz’s Role in the Development of Complementary Dispute Resolution, 7 Seton Hall Const. L.J. 2, 335-39 (Winter 1997).

In 1987, he appointed a successor Task Force on Dispute Resolution to build upon the work of its predecessor Committee and develop the framework for use of dispute resolution mechanisms that were systematic and reasonable. Following review by the public, the Bar, and the vicinages, the Court adopted the recommendations of the Task Force.

The objective of the CDR program is to provide citizens with a full range of options to resolve disputes, including traditional litigation as well as a variety of complementary processes. The CDR program aims to improve public access to justice, reduce delays and costs for litigants, increase the quality and efficiency of delivering justice, and help deal with demands of growing caseloads.

The Supreme Court adopted the Comprehensive Justice Program (the Master Plan) as the structure for developing, implementing, and managing CDR programs by the vicinages.

As summarized by former Associate Justice, Marie L. Garibaldi, the goals for each CDR program were:

Be as accessible as possible to all disputants and not favor one group or segment; protect the legal rights of all participating disputants; provide a fair and competent mechanism for resolving disputes; be an effective forum for the enforcement of law, including formulating outcomes in terms that are conducive to subsequent enforcement as necessary; and be as efficient as possible in terms of the cost and time required of both the system and the disputants. [Id. at 337.]

In 1980, concerned by the large number of defendants held in pre-trial detention, the Chief Justice formed the Supreme Court Committee on Speedy Trial. Six years later, at the first judicial conference held in Parsippany, New Jersey, speaking before judges, vicinage and municipal support staff, prosecutors and public defenders, he reported on the project’s success by noting:

I am convinced beyond any doubt that there is no fundamental conflict between speedy trial and the quality of justice. The conflict, if any, is between the management of Speedy Trial and the quality of justice. My personal commitment to Speedy Trial has been and remains total – perhaps too total. In terms of society’s perceived needs, Speedy Trial has the absolutely highest priority in the administration of justice. [49 Rutgers Law Review 927 (Spring 1997).]

In 1986, the Task Force on Speedy Trial issued its report and included "a series of standards pertaining to case management, time goals, case initiation, first appearances, prosecutorial screening, pretrial intervention and early case disposition, arraignments, pretrial conferences, plea dispositions, firm trial lists, sentencing and backlog reduction. Many of those standards were subsequently adopted as Criminal Justice Operating Standards in 1992." Report of the Joint Committee on Criminal Justice, March 10, 2014, page 72. See Pressler, Current N.J. Court Rules, comments to Rules 3:2-1, 3:9-1, 3:9-3(g), and 3:13-3 (1996).

Equality and Fairness

Committed to equality and fairness to the citizens employed by the Judiciary and to the citizens who access the court system, in 1984, Wilentz convened an internal Ad Hoc Committee on Minority Concerns. The Committee was chaired by Judge James H. Coleman, Jr., Appellate division. Judge Coleman in 1981 was the first minority appointed to the Appellate Division and in 1994 was the first minority named to the New Jersey Supreme Court. In August 1984, the committee submitted its Report of the Committee on Minority Concerns (Coleman Committee Report) to the Supreme Court. In a statement issued with the final report, Wilentz commended the Task Force by stating "it had performed a public service of the highest order." Speaking in more general terms, he noted: The Judiciary’s efforts in this area have been of long standing and have been substantial. This report gives us new direction and new motivation. The mere existence of bias must be a matter of great concern to an institution dedicated to fairness and equality. … It must be eradicated, no matter how difficult that may be and no matter how long that may take. If there is to be one place in our society that is to be totally, completely free of bias, it must be the courts and the court system. [Release by Administrative Office of the Courts, August 9, 1992.]

One year later, Wilentz appointed a sixteen member Task Force on Minority Concerns. In January 1986, the Task Force was expanded to forty-eight members. The Task Force issued an interim report in 1989 and a final report in 1992. The Final Report included sixty-three recommendations of which fifty-three were approved in some form for implementation. In August 1992, the committee submitted its report to the Supreme Court. See New Jersey Judiciary Minority Concerns Program.

In a statement issued with the final report, Wilentz commended the Task Force by stating "it had performed a public service of the highest order." Speaking in more general terms, he noted:

The Judiciary’s efforts in this area have been of long standing and have been substantial. This report gives us new direction and new motivation. The mere existence of bias must be a matter of great concern to an institution dedicated to fairness and equality. … It must be eradicated, no matter how difficult that may be and no matter how long that may take. If there is to be one place in our society that is to be totally, completely free of bias, it must be the courts and the court system. [Release by Administrative Office of the Courts, August 9, 1992.]

On August 16, 1993, one year following the public release of the final report, Wilentz announced the establishment of local advisory committee on minority concerns in each of the fifteen vicinages and at the Administrative Office of the Courts. The Supreme Court Committee on Diversity, Inclusion, and Community Engagement ("the SCCMC") is one of eight standing committees. Under the Operational Guidelines, the committee reports to the court every two years.

One of Wilentz’s actions on improving equal access and equal justice included creation of the Supreme Court Task Force on Municipal Courts. The Task Force report was released in July 1985 and became a blueprint for reforming the state’s municipal court system. That year, a new Municipal Courts Division and a director were added to the Administrative Office of the Courts; four municipal presiding judges, the state’s first, were appointed the next year. Additional reforms, in later years, included expanding automation of municipal court functions, sanctioning plea bargains in non-DWI cases, and providing indigent municipal court defendants with counsel via Court order that subjected all New Jersey lawyers to pro bono assignments. [author needed], Municipal Court Reform, 7 Seton Hall Const. L.J. 2, 424-25 (Winter 1997).

Retirement

In his written statement announcing his retirement on June 13, 1996, Wilentz enunciated his view on the importance of an independent judiciary to best serve the citizens of New Jersey:

We have a fine court system, still supported by the people of New Jersey in these somewhat difficult times. That support is one of our most important sources of strength. The ultimate source of our strength and integrity remains our own commitment to judicial independence, total and uncompromising. Retirement Statement, June 13, 1996, 49 Rutgers L. Rev. 1213 (Spring 1997)].

Chief Justice Wilentz retired from the New Jersey Supreme Court on July 1, 1996 due to a disabling cancer. He passed away barely three weeks later on July 23, 1996.