- Term: Jan. 19, 1956 - Aug. 31, 1973

- Status: Deceased - Feb. 5, 1977

Introduction

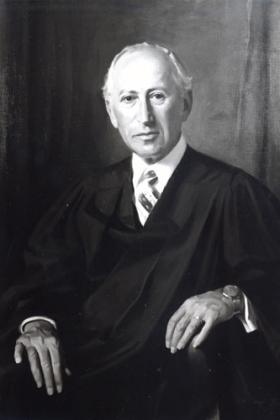

Chief Justice Joseph Weintraub was the second Chief Justice of New Jersey’s modern Supreme Court under the 1947 Constitution. Arthur T. Vanderbilt had left large shoes, and Weintraub filled them well, yet with his own distinctive style. Weintraub was appointed to the Supreme Court as an Associate Justice in 1956 to replace Justice William J. Brenan, Jr. who had been appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Less than two years later, following the untimely death of Vanderbilt, Weintraub replaced him as Chief Justice on August 19, 1957.

During his 16 years as Chief Justice, Weintraub was every bit as aggressive as Vanderbilt in leading New Jersey’s courts into the modern world, and in asserting the Judiciary’s role as an equal, independent branch of state government. Equally important, under Weintraub’s leadership, New Jersey’s Supreme Court led the nation in adapting the common law and state constitutional law to the changing needs of society. Proceeding on the premise that the law should be stable, but not petrified, the Weintraub Court addressed issues pertaining to products liability, negligence, affordable housing, the landlord-tenant relationship, criminal law, and public school financing.

The financing of public education may be the single most important issue addressed by the Weintraub Court. In his 1973 watershed ruling in Robinson v. Cahill, Weintraub confirmed that our State Constitution means what it says when it guarantees a “thorough and efficient system of free public schools." His decision remains a clarion call reminding everyone of the constitutional obligation to educate our children. Though New Jersey continues to struggle with the financing of public education, it was the Weintraub Court which prodded New Jersey’s conscience on the Constitutional imperative to fund schools in a responsible manner.

Overview of Weintraub’s Life and Legal Career

Joseph Weintraub was born in Cranford, N.J. on March 5, 1908. The son of Jewish immigrants who had fled the "programs" of Russia, he grew up in Newark in a family of limited means. His father died when Weintraub was five years old, leaving his mother to support the family by running a produce store.

When twelve-years old, Weintraub started working as an office boy at the Law Firm of Stein, Hannoch and McGlynn, where partner Edward McGlynn, virtually adopted him, paying the cost of his undergraduate and law school education at Cornell.

Weintraub graduated from Barringer High School in Newark in 1924 at the age of sixteen. The class of 1924 was impressive; another graduate was William J. Brennan, Jr., who served on both the New Jersey Supreme Court and the United States Supreme Court from 1956 to 1990. Joseph Weintraub replaced Brennan on the New Jersey Supreme Court.

The Barringer High yearbook shed some interesting light on Weintraub, stating the following about him: "Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers," his ambition was "to be a lawyer;" his weakness was that he was "argumentative," his amusement was "cases in court," he succeeded by "arguing." See Daniel J. O'Hern, "Brennan and Weintraub: Two Stars to Guide Us," 46 Rutgers Law Journal, 1049, 1050 (1994).

In the Fall of 1924 Weintraub began a life-long association with Cornell University. He entered the seven year arts-law program, earning his B.A. degree in 1928. His undergraduate work was exemplary as evidenced by his induction into Phi Beta Kappa and Phi Kappa Phi. Weintraub also excelled in oral presentations, winning the Class of 1886 Memorial Prize in Public Speaking, and competing as a finalist in the Class of 1894 Memorial Contest in Debate. See John J. Francis, Joseph Weintraub, A Judge for all Seasons, 59 Cornell Law Review 186 (1974) 186; W. David Curtiss, Chief Justice Joseph Weintraub - Cornelian, 59 Cornell Law Review 183 (1974) 183.

In September 1927, Weintraub started his studies at Cornell Law School. Like most first year law students his perception differed from the reality of the study of law. He later said: When I entered law school, I expected to receive a slide rule of sorts with which to find simple and certain answers. I recall my early disappointment, and how I settled for statements of the majority rule, minority and sub-minority rules, and how I viewed suspiciously the professor who seemed to enjoy tormenting his class with provocative problems and nary an answer to any of them. See Joseph Weintraub, Judicial Legislation, 81 N.J.L.J. 545.

During his first year, Weintraub was on the winning team in the Moot Court competition. The following year he was selected as a Boardman Scholar, awarded to the ranking law student at the end of the second year. In his final year, he served as Editor-in-Chief of Cornell Law Quarterly; was inducted into the Order of the Coif; and graduated first in the Class of 1930. Later in life he served fifteen years (1958-1973) as a member of the school's Advisory Council. See Curtiss, supra 184; John W. Bissell, Chief Justice Weintraub Lecture April 10, 2002, 14.

During his final year on the Law Review, Weintraub published an article on commercial law that came to the attention of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who wrote to Weintraub complimenting him on the article. NJ Supreme Court Justice John J. Francis recalled the pride that his Chief took in the Brandeis letter. "I think he was prouder of that letter than anything else that ever happened to him. He had that letter framed and always displayed it in whatever office he occupied." See Curtiss, supra 184; John J. Francis, Chief Justice Joseph Weintraub: A Tribute, 30 Rutgers Law Journal 479 (1977) 479.

Weintraub was admitted to the New Jersey bar in 1930 and practiced law with the McGlynn firm, focusing on appellate work. In March 1943, during World War II, he was inducted into the army as a private; when he left the service in 1946 he had attained the rank of captain. He remained single until he married his wife, Rhoda in 1960.

A major turning point in his professional life was his appointment as Counsel to Governor Robert Meyner, during which time he also served as a member of the Bi-State Waterfront Commission. In 1956, Governor Meyner appointed him as a Judge of the Superior Court and six months later as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. Following the death of Arthur T. Vanderbilt, Meyner appointed Weintraub as Chief Justice on August 19, 1957.

Weintraub’s Tenure Begins

In the wake of Winberry v. Salisbury, 5 N.J. 240 (1950) which reserved to the Supreme Court the power to make rules concerning practice and procedure in the courts, a controversy emerged between the judiciary and the executive and legislative branches over which branch had the authority to adopt rules of evidence.

As a senator, governor, and ultimately as a lawyer, Governor Meyner severely criticized the Winberry decision. Following Weintraub’s appointment as Chief Justice, the opportunity arose for a resolution of the stalemate on the adoption of evidence rules.

With his former counsel ensconced as Chief Justice, Meyner expressed the hope in his 1959 "State of the State" address that the Legislature and the Supreme Court could resolve the conflict over the method of adoption of the rules of evidence. Nothing happened. Then, in his 1960 "State of the State" address, Governor Meyner urged the Legislature to adopt the Evidence Act.

The Legislature responded by passing the Evidence Act of 1960, which Governor Meyner promptly signed

"The Act authorizes the Supreme Court to adopt rules of evidence. First, the court may discuss any such rules at its annual judicial conference and then publish them by September 15. The rules will become law the following July, unless the Legislature vetoes them by a joint resolution signed by the Governor. Second, by a joint resolution similarly signed, the Legislature may authorize the court to adopt rules by submitting them to the judicial conference. Finally, by joint resolution, the Legislature may reduce or eliminate the time period for the legislative veto." Pollock, Forward: Celebrating Fifty Years of Judicial Reform Under the 1947 New Jersey Constitution, 29 Rutgers Law Journal 675, 694. Thus, Weintraub participated in bridging the gap between the Supreme Court and the other two branches of government on a potentially divisive issue.

During his service on the Supreme Court, Weintraub was a prolific opinion writer. He wrote for clarity and understanding. Realizing that opinions serve as guides for lawyers and judges Weintraub wanted his opinions to be useful. He wrote:

"I like little words. They are spry; they dance; they paint pictures. I would not use a multi-syllable word when a four letter word would do. A succession of ponderous words, usually of Latin derivation, lumbers along. They are drab and their weight delays the reader." J. Weintraub, Writing, Consideration & Adoption of Opinions, paper delivered at Conference of Chief Justices, Baltimore, Maryland, August 24, 1960, quoted in Francis, Joseph Weintraub, A Judge For All Seasons, 59 Cornell L. Rev. at 193.

United States District Court Chief Judge John W. Bissell concurred with that assessment. "Justice Weintraub favored brief opinions, written clearly, in language that was readily comprehensible to the lower courts, to the bar, to the parties and the public. They are pictures of clarity which most certainly served as a guide and inspiration to his colleagues in the crafting of opinions assigned to them." John W. Bissell, "Chief Justice Weintraub Lecture" April 10, 2001, 14; See Francis, supra 187, 193.

Notable Opinions

The breadth of Weintraub’s opinions was as wide as his knowledge of the law. In Jackman v. Bodine, 55 N.J. 371 (1964), he wrote the sixth in a series of opinions addressing the apportionment of the State Legislature. The opinion rejected an equal protection challenge and sustained the apportionment plan in the New Jersey Constitution.

Weintraub brought to civil law the same realism that he brought to reviewing criminal cases. Thus, in State v. Shack, 58 N.J. 297 (1971), Weintraub addressed the plight of migrant farm workers. Shack, a public interest lawyer with Camden Regional Legal Services, sought to consult with migrant workers at a worker’s labor camp on a private farm. The owner charged Shack with trespass. In defense, Shack asserted that the trespass statute unconstitutionally violated both his and the farm workers’ First amendment rights. Weintraub found the constitutional claims uncertain and “a decision in non constitutional terms is more satisfactory." Id. at 303.

Focusing on the farm owner’s reliance on his property rights to sustain the claim of criminal trespass, Weintraub wrote: “…we are satisfied that under our State law the ownership of real property does not include the right to bar access to governmental services available to migrant workers and there was no trespass within the meaning of the penal statute."

For Weintraub, “Property rights serve human values." Ibid. Recognizing that the farm workers “are rootless and isolated", Weintraub sought “a fair adjustment of the competing needs of the parties, in the light of the realities of the relationship between the migrant worker and the operator of the housing facility." 58 N.J at 307. He acknowledged that the farmer “is entitled to pursue his farming activities without interference….But we see no legitimate need for a right in the farmer to deny the worker the opportunity for aid available from federal, State, or local services or from recognized charitable groups seeking to assist him." Ibid. The employer could reasonably require a visitor to identify himself and state his purpose, “but the employer may not deny the worker his privacy or interfere with his opportunity to live with dignity and to enjoy associations customary among our citizens."

In Shack, the driving force of the opinion was the reality of the relationship between the migrant workers and the labor service, a relationship steeped in inequality. The inequality in bargaining positions also drove the opinions of the Weintraub Court when abolishing the requirement of “privity" (a direct contractual relationship) between an automobile manufacturer and a consumer of a defective automobile. Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors, Inc., 32 N.J. 358 (1960); barring a major oil company from terminating its relationship with a service station operator absent a showing that the operator had failed substantially to perform his obligations, Marinello v. Shell Oil Co., 63 N.J. 402 (1973); precluding a real estate broker from recovering a commission from a property owner absent a showing that a prospective buyer was financially able to close. Ellsworth Dobbs, Inc. v. Johnson, 50 N.J. 28 (1967). Implicit in those opinions is the rationale that courts are not to be instruments of injustice and that strict enforcement of contracts as written, absent a consideration of the comparative status of the parties, may be contrary to the public interest.

Robinson v. Cahill: School Funding

Weintraub’s analytical genius is revealed in the initial Robinson v. Cahill decision, 62 N.J. 473 (1973). The trial court had invalidated New Jersey’s system for funding public education under both the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and the guaranty of fundamental rights (which does not expressly mention “equal protection") in Article 1, paragraph 1 of the New Jersey Constitution. Before the New Jersey Supreme Court could review the trial court order, the U.S. Supreme Court decided San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973) which held that the Fourteenth Amendment’s guaranty of equal protection did not protect public education.

With relief under the U.S. Constitution foreclosed, Weintraub turned to state law. He was concerned that relying on notions of equal protection under the New Jersey Constitution could create problems when considering other essential governmental activities encompassed by protection of general welfare, such as police and fire protection, water, and public health. Such services, like public education, are vital. Aware of the competition for state funds for such services, the Court avoided reliance on the guaranty of equal protection, and relied instead on the specific constitutional guaranty of a “thorough and efficient system of free public schools" in Article VII, Section 4, paragraph 1 of the New Jersey Constitution. The effect was to limit the holding to public education without creating problems for the financing of other governmental activities. See Pollock, Keynote Address, Financing Our Future: Education Improvements for the 21st Century, Annual Survey of American Law, 1998 Volume, Issue 2.

The Robinson v. Cahill opinion reflects Weintraub’s view of the relationship between the judicial, executive, and legislative branches of state government. Justice John Francis summarized Weintraub’s view of that relationship:

Throughout his years on the Court, he remained acutely aware of the line of demarcation between the judicial and legislative branches of government, and of the duty of the judicial branch to refrain from encroaching on the area of operation of the legislative branch. So, if a statutory rule or doctrine were in question before the Court, even it appeared to be inadequate to serve the needs of the times, he would declare that the remedy was in the hands of the Legislature, and the Courts should not interfere. But, if a common law doctrine were involved and it was out of tune with the needs of modern society, he was quite ready advocate change so as to adapt it to existing needs and ideals, without waiting for legislative action. Proceedings before the Supreme Court of New Jersey in memory of Chief Justice Joseph Weintraub, May 24 1977 XXVIII-XXIX. One exception to that description of the Weintraub’s respect for the separation of powers was that if legislative action or inaction violated constitutional rights, as did the legislative response to the mandate to provide for a thorough and efficient system of free public education, the judiciary must remedy the wrong.

Criminal Law

On criminal law, Weintraub started from “the forgotten right, the right to protection from criminals." John Kolesar, Ex-N.J. Chief Justice Weintraub; often made state judicial history, Trenton Times, Feb. 7, 1977, at B5, quoted in O’Hern, Some Reflections on the Roots of the differing Judicial Philosophies of William J. Brennan, Jr. and Joseph Weintraub, 46 Rutgers L. Rev. 1049 (1994). Weintraub wrote: “It bears repeating that the first right of the individual is to be protected from criminal attack, that is the reason for government. The responsibility to that end rests no less upon the judiciary than upon its coordinate branches. State v. Gerardo 53 N.J. 261 (1969). That approach led Weintraub to disagree with the U.S. Supreme Court when, in Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961) it adopted the exclusionary rule, which barred evidence seized in violation of the Fourth Amendment. Previously, in Eleuteri v Richman, 26 N.J. 596, cert. denied 358 U.S. 843 (1958), Weintraub had rejected a rule requiring the suppression of evidence obtained by illegal searches and seizures.

He later wrote: To set criminals free is to exact a price, not from some pain-free societal entity, but from innocent individuals who will be their next victims. There are other hurts as well, for the suppression of proof of guilt must weaken respect for the reach of the law, thereby increasing the toll of victims and injuring as well those offenders who might have been deterred from a career of lawlessness. Some would add their belief that current doctrines tend to corrupt officials who, struggling to cope with the dirty realities of crime, strain to bring the facts within unrealistic concepts. These trespasses upon the first right of the individual to be protected from attack should not be suffered unless it is plain that some larger individual value is served. State v. Gerardo, 53 N.J. 264 (1969) application of bail denied, 400 U.S. 589 (1970).

When sustaining the conviction of a defendant who had confessed after receiving Miranda warnings, Weintraub wrote, “The Constitution is not at all offended when a guilty man stubs his toe." State v. McKnight, 52 N.J. 35 (1968). Weintraub viewed as fundamental “the right of the individual to live free from criminal attack in his home, his work, and the streets." State v. Davis, N.J. (1967) cert. denied 389 U.S. 1054 (1968). To that extent, Weintraub perceived the judiciary as an extension of law enforcement. That view sometimes put him at odds with the U.S. Supreme Court which, during Weintraub’s tenure as Chief Justice, extended the protection of the U.S. Constitution to criminal defendants.

In a concurring opinion in State v Lucas 30 N.J. 37, 74 (1959), he defended the retention of the M’Naghten rule for determining whether a defendant was criminally insane and therefore not guilty of murder. The M’Naghten rule provides a defense if “at the time of committing the act, the party accused was laboring under such a defect of reason from disease of the mind as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing was wrong…." Id at 66. Confronted with alternative theories for determining insanity and with conflicting psychiatric testimony on whether the defendant satisfied the M’Naghten rule, Weintraub wrote in favor of the rule’s retention, explaining that additional psychiatric testimony could be adduced at sentencing.

In State v. Carter, 54 N.J. 436 (1969) Chief Justice Weintraub’s opinion affirmed the murder convictions of two men. Three people were murdered in an after-hours bar in Paterson. One of the defendants was Rubin “Hurricane" Carter, a professional boxer with hopes of attaining the Middleweight boxing championship. Carter and co-defendant, John Artis were convicted of murder. Weintraub’s opinion held that a detective’s testimony regarding poor quality notes taken during the interrogations of both defendants did not violate the prohibition of the use of a codefendant confession against another codefendant. It also held that the warrantless search and seizure of the vehicle was permissible, finding the arrest of the defendants supported by probable cause, and the car properly searched as an incident to arrest.

Ultimately the Court determined that the trial was not perfect, but it was fair in light of Weintraub’s policy preference giving weight to the “first right of the individual to be protected from criminal attack." State v. Carter, at 450. In 1976 the New Jersey Supreme Court determined that the right to a fair trial for Carter and Artis was prejudiced, and ordered a new trial [65 N.J. 420 (1976)]. After a second trial found both men guilty of first degree murder, the case made it back to the New Jersey Supreme Court twice more [85 N.J. 300 (1981); 91 N.J. 86 (1982)]. The legal proceedings of Rubin “Hurricane" Carter, chronicled in a movie and in song by Bob Dylan, ended in 1985. Carter and John Artis were released on federal writs of habeas corpus based upon the prosecutor’s failure to disclose inconsistent polygraph evidence, and the violation of Carter’s due process rights based on the prosecution’s improper appeal to racial prejudice. See Carter v. Rafferty, 621 F. Supp. 533 (1985).

Notwithstanding Weintraub’s emphasis on protection of the public from criminal conduct, he remained committed to fairness and the search for truth in criminal prosecutions. Thus, in State v. Johnson, 28 N.J. 144 (1958), appeal dismissed, 368 U.S. 145, cert denied, 368 U.S. 933 (1961), he wrote for the court in approving a defendant’s motion for discovery of his pre-trial statements and confessions:

We start from the premise that truth is best revealed by a decent opportunity to prepare in advance of trial….It is of no moment that pretrial inspection is not constitutionally assured….We are not limited to constitutional minima; rather we strive for practices which will best promote the quest for truth. 28 N.J. at 136-37.

Although Weintraub disagreed vigorously with the U.S. Supreme Court in its approach to criminal law, his respect for that Court as an institution remained strong. Thus, he led the conference of State Chief Justices in defeating a criticism of that Court for its decisions. A deep sense of propriety and fairness, whether in according criminal defendants a fair trial or in disagreeing with the U.S. Supreme Court on decisions in criminal law, pervades Weintraub’s jurisprudence.

Judges and Justices, although guided by legal principles, inevitably reflect their time, place, personal experiences and values. That reflection is manifest in the evolution of judicial decisions. For example, in a 1970 per curiam opinion, the Weintraub Court unanimously ruled that a prosecutor’s exercise of peremptory challenges excusing all three prospective black jurors, without more, did not establish the systematic exclusion of blacks from the jury. State v. Smith, 55 N.J. 476 (1970). The prosecution arose in the wake of the Newark riots in 1967, which “were said by some to have been triggered by the defendant’s arrest." Id at 481. Defendant was a black taxi driver and the arresting officers were white. The facts surrounding the arrest of defendant, who was convicted of assault and battery on one of the officers, were sharply contested. In its ruling, the Court did not consider whether the prosecution’s use of peremptory challenges based solely on race, rather than individual bias, would violate the New Jersey Constitution. State v. Gilmore, 199 N.J. Super. 389, 396 (App. Div. 1985)

Sixteen years later, the Supreme Court, without expressly overruling State v. Smith, reversed the robbery conviction of a black defendant because an assistant prosecutor systematically excluded all nine black prospective jurors. In reaching that result, the Court affirmed “the judgment in the well-reasoned opinion of the Appellate Division," 103 N.J. 518 (1986) written by Judge, later Justice, William Coleman. In Gilmore, both the Appellate Division and the Supreme Court relied on “the defendant’s constitutional right to trial by an impartial jury under Article 1 of the New Jersey Constitution." 103 N.J., supra, at 524. In the interim between the decisions in Smith and Gilmore, the Court gained an enhanced appreciation of the preservation of the fairness of the conduct of criminal justice system, particularly as it affected minority defendants.

At oral argument, Weintraub dominated the interaction with counsel. Justice Francis described that interaction: When a question was asked and an unresponsive answer begun, Chief Justice Weintraub, whose mind had been churning along at jet speed, occasionally said “No, no, no." and pressed for a direct answer. Some attorneys without much experience in oral arguments were heard later to express the reaction that the Chief Justice’s spontaneous remarks were sharp or disparaging. Nothing could be further from the truth. Persons aware of his disposition for kindness and compassion know his rejective comment was instinctive and impersonal, and arose from his complete dedication to the true function of the court. In fact, if counsel appeared flustered or upset, no one moved in more quickly or sympathetically to help him out than the Chief Justice. 59 Cornell Law Review 186, 197.

On August 31, 1973 Joseph Weintraub retired from the New Jersey Supreme Court. On February 5, 1977 he died in a hospital in Miami, Florida. He was survived by his wife, his brother, Charles, and his two sisters, Frances Finkle and Yetta Rozman. His funeral was held at Temple B'nai Jeshurun in Short Hills, New Jersey on February 8, 1977. See The New York Times, February 7, 1977 obituary.

Talented Associate Justices

In addition to Weintraub, the Court consisted of several other very talented Associate Justices. Three of those Associate Justices, Nathan Jacobs, John Francis, and Thomas Schettino shared chambers with Weintraub at the Mutual Benefit Insurance Building, Broad Street, Newark. The Weintraub Court consisted of four Democrats (Chief Justice Weintraub and Associate Justices Francis, Hall, and Schettino) and three Republicans (Associate Justices Haneman, Jacobs, and Proctor). Ever since its creation, the Court has never had more than four Justices from either of the two major political parties. Usually, this has meant that the Court is divided between four Justices from one of the major political parties and three from the other party. Every Governor has honored this tradition, which reinforces both the reality and public perception of the judicial independence of the Supreme Court from political influence.

Nathan Jacobs

Justice Nathan Jacobs preceded Weintraub on the Supreme Court, serving from March 13, 1952 to February 27, 1975. He was born in Russia on February 28, 1905, and immigrated to the United States when he was 4 or 5. Jacobs graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. In 1928, he graduated magna cum laude from the Harvard Law School, where he was on the Law Review. While practicing law in the firm of Arthur T. Vanderbilt, he earned a degree as doctor of laws at Harvard.

With the repeal of Prohibition, Jacobs served as Deputy Commissioner and General Counsel for the New Jersey Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control. During World War II, he organized and administered the New Jersey Division of the Federal Office of Price Administration. At the 1947 constitutional convention, Jacobs was appointed as Vice-Chairman of the Judiciary Committee. The Chairman became ill, so Jacobs became the acting Chairman, and with input from Arthur Vanderbilt, drafted the judicial article of the Constitution. Driscoll appointed Jacobs first to the former Supreme Court, then, under the 1947 Constitution, to the Superior Court, where he served on the Appellate Division, and finally to the Supreme Court.

Two principles resonating in Jacobs’ opinions are that the common law should adapt to changes in society and that the law is imbued with the principle of fundamental fairness. Justice Jacobs invoked both principles in Collopy v. Newark Eye and Ear Infirmary, 27 N.J. (1958), in which the Court discarded absolute immunity for nonprofit eleemosynary institutions, such as hospitals. Two other opinions demonstrate Jacobs’ belief that the common law should adapt to society’s evolving sense of justice. Breen v. Peck, 28 N.J. 351 (1958) held that release of one tortfeasor did not necessarily bar a subsequent action against a joint tortfeasor, a holding that rejected a rule embedded in the common law of England and New Jersey. In Ekalo v. Constructive Service Corporation of America et al., 46 N.J. 82, Justice Jacobs considered “in these modern times of interspousal equality" that a wife could maintain a claim for loss of consortium not only where a tortfeasor had injured the husband intentionally, but also where the injury resulted from the tortfeasor’s negligence. Underlying all three opinions were “pertinent policy considerations…expanding tort liability in the just effort to afford decent compensatory measure to those injured by the wrongful conduct of others." Id. at 93.

John Francis

Justice John Francis was born on June 19, 1903 in Orange, New Jersey, and graduated from Rutgers Law School in 1925. He earned an LL.M from New York University Law School in 1948, and received an honorary doctorate from Rutgers in 1959. As a lawyer, he enjoyed an active trial and appellate practice. Fulfilling a lifelong interest in becoming a judge, he was appointed to the former Essex County Court in1948, to the Superior Court in 1952, and the Supreme Court in 1957, where he served until 1972.

He wrote several significant opinions for the Court, most notably Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors, 32 N.J. 358 (1960), which abolished privity as an element of an action for personal injuries caused by a defective product and thereby gave rise to the modern law of products liability. Dean Prosser has described the effect of Henningsen as causing “unquestionably the most sudden and spectacular overturn of a well-established rule of law in the entire history of the law of torts." Prosser, The Fall of the Citadel (Strict Liability to the Consumer), 50 Minn. L. Rev. 791 (1969).

Thomas Schettino

Justice Thomas Schettino was born on September 9, 1907, in Newark, graduated from Rutgers University in 1930, and from Columbia Law School in 1933. He served on the Supreme Court from March 20, 1959 until September 9, 1972. Before that he had served in several important appointed positions. From 1936 until 1941 he was a member of the law department of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and from 1942-44, he was Executive Clerk to Governor Charles Edison. He then practiced law until his appointment to the former Court of Errors and Appeals on which he served until 1947, when he was appointed to Superior Court, on which he served from 1948 to 1959, when Governor Meyner appointed him to the Supreme Court. Unfortunately, he was stricken with Parkinson’s disease and resigned from the Court in September, 1972. He died on March 21, 1983. Notwithstanding his debilitating illness, he wrote 122 majority opinions while on the Supreme Court, and earned a reputation for friendliness and compassion.

Haydn Proctor

A fourth Justice, Haydn Proctor combined scholarly skills with those of a practical politician. A lifelong resident of Monmouth County, he graduated from Lafayette College and Yale Law School, where he was a member of the Yale Law Journal. He served as President of the Senate, Acting Governor, and Associate Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court.

In Bexiga v. Havir Manufacturing Corp., 60 N.J. 402 (1972), he wrote that the manufacturer could be strictly liable for the defective design of a press without a safety device unless the failure to install the device would render the press unusable for its intended purpose. Bexiga, an employee injured because of the absence of a safety device on the press, could not be barred by contributory negligence when injured by the absence of the device.

In a refreshing demonstration of candor, Justice Proctor changed his mind on the issue of interspousal immunity, writing in Immer v. Risko, 56 N.J. 382 (1970) that a wife injured by her husband’s negligent operation of an automobile could sue him for her injuries. Twelve years earlier he had joined a four-person majority in denying such claims. Koplik v. C.P. Trucking Corp., 27 N.J. 1 (1958). In Immer, he explained that he was no longer persuaded by the two policy considerations that undergirded the earlier opinion. Those two considerations were that such suits might be a threat to domestic peace and that allowing them could lead to the possibility of fraud. Justice Proctor explained that domestic peace was threatened as much by disallowing such suits as by permitting them and that he did “not believe that the possibility of fraud should any longer be deemed sufficient to bar all interspousal tort claims without at least an opportunity to determine whether our courts can deal adequately with the problem." 56 N.J. at 493.

Vincent S. Haneman

Vincent S. Haneman served on the Weintraub Court from 1960 to 1971. Justice Haneman was born in Brooklyn on April 25, 1902 and raised in East Orange. A graduate of Syracuse Law School, he enjoyed an extensive career in public service having served as mayor of Brigantine from 1934-42, an assemblyman for seven years, and as counsel to the New Jersey Racing Commission from 1940-44. In 1944, he was appointed to the Court of Common Pleas, and to the New Jersey Superior Court in 1947, and then to the Supreme Court. He died on January 10, 1978, while on the way to his winter home in Naples, Florida.

Among his opinions is Palisades Properties v. Brunetti, 44 N.J. 117 (1965), which introduced to New Jersey contract law the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. Justice Haneman wrote that in every contract there is an implied covenant that: neither party shall do anything which will have the effect of destroying or injuring the right of the other party to receive the fruits of the contract; in other words, in every contract there exists an implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. Where fairness and justice require, Even though the parties to a contract have not expressed an intention in specific language, where fairness and justice require, the courts may impose a constructive condition to accomplish such a result when it is apparent that is necessarily involved in the contractual relationship. 44 N.J. at 130. By adapting law to the changing circumstances surrounding a contractual relationship and bending contracts to notions of fairness and reason, Brunetti transformed the law of contracts as Hennigsen, Collopy, Bexiga, Immer, and other opinions transformed the law of torts.

Frederick W. Hall

Justice Frederick W. Hall was born on February 22, 1908 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. At the age of five, he began his education in the third grade in Neshanic, New Jersey. He graduated from Rutgers, second in his class, and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. In 1931, he graduated Cum Laude from Harvard Law School. One of his law school classmates was William Brennan, who earlier had been a Barringer High School classmate of Joseph Weintraub.

On graduating from Harvard, Justice Hall, like Justice Jacobs, began a clerkship in the office of Arthur T. Vanderbilt. In 1941, he joined in the formation of the firm of Wharton & Hall in Somerville. In addition to practicing law, he served in Bound Brook as a member of the Planning Board and School Board. He was appointed to the Superior Court in 1953, and ultimately served as the Assignment Judge in five counties. In 1959, he was appointed to the Supreme Court, where he served until 1975.

His deep knowledge of municipal and land use law provided an informed background in his landmark opinion for the Court, Southern Burlington County NAACP v. Township of Mount Laurel, 67 N.J. 151 (1975) (“Mt. Laurel I"), which held that a zoning ordinance that contravened the general welfare, notably by excluding housing for low income housing, violated the “general welfare" clause of Article 1, Section 1 of the New Jersey Constitution.

As Justice Hall wrote: "The legal question before us, as earlier indicated, is whether a developing municipality like Mount Laurel may validly, by a system of land use regulation, make it physically and economically impossible to provide low and moderate income housing in the municipality for the various categories of persons who need and want it and thereby, as Mount Laurel has, exclude such people from living within its confines because of the limited extent of their income and resources. Necessarily implicated are the broader questions of the right of such municipalities to limit the kinds available housing and of any obligation to make possible a variety and choice of types of living accommodations. We conclude that every such municipality must, by its land use regulations, presumptively make realistically possible an appropriate variety and choice of housing. More specifically, presumptively it cannot foreclose the opportunity of the classes of people mentioned for low and moderate income housing and in its regulations must affirmatively afford that opportunity, at least to the extent of the municipality’s fair share of the present and prospective regional need therefore. 67 N.J. at 173-74."

Although best known for his Mt. Laurel I opinion, Justice Hall also wrote several other leading opinions. In Heavner v. Uniroyal, Inc., 63 N.J. 130 (1973), he wrote a leading opinion on choice of law when the choice was between the law of New Jersey as the forum and that of a foreign jurisdiction. The opinion discarded the mechanical application of the law of forum in favor of a more nuanced approach:

"We need go no further now than to say that when the cause of action arises in another state, the parties are all present in and emendable to the jurisdiction of that state, New Jersey has no substantial interest in the matter, the substantive law of the foreign state is to be applied, and its limitation period has expired at the time suit is commenced here, New Jersey will hold the suit is barred. In essence, we will ‘borrow’ the limitations law of the foreign state. 63 N.J. at 141."

In sum, the Weintraub Court fulfilled the promise of the Vanderbilt Court for an independent judiciary ready to adapt the law to the evolving needs of modern society. Under Vanderbilt, the Court established its independence from legislative control on practice and procedure of the judiciary. Under Weintraub, the Court exercised its independence to meet the needs of consumers, school children, low and moderate income families, and others who did not have ready access to the other branches of government.